Russia's Irreversible Path into Totalitarian State

War is not a contingency in today’s Russia; it is the operating system. Anyone who believes they can bring back Russia to "normal" is just delusional

With Trump’s efforts towards peace in Ukraine, there is a growing hope among European and especially American elites that ceasefire will bring back Russia to its pre-2020 state. But what they miss is that the Russian state now runs on a different logic — security agencies, law, and code working in tandem to surveil, mobilize, and punish. Russia has crossed the threshold from autocracy to a durable digital totalitarianism. Western strategies premised on a coming “thaw” will fail, and any belief to reverse Russian course is just a wishful thinking.

Disclaimer: this post is covered by CC0 license. Do whatever you want with it, as long as message from here is delivered.

Elite Purges in Russia

On July 7, 2025, Russia’s political elite was stunned by an unprecedented event: the Minister of Transport, Roman Starovoyt — a former governor of Kursk Region — shot himself in a parking lot while trying to escape arrest in a corruption case. It was the first suicide of such a high-ranking official since the 1990s. This high-profile incident laid bare deep frictions within the Russian elite, who are experiencing the most extensive purges by the security apparatus — above all by the FSB — since the Stalin era. Starovoit was not the first to face a possible prison term.

Since mid-2024, when Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu was dismissed and effectively stripped of influence, a growing wave of repression has swept Russia, marked by several high-profile cases. For example, Dmitry Kurakin, the former head of the Defense Ministry’s Department of Property Relations, was sentenced to 17 years in a high-security penal colony for taking bribes. Former Deputy Defense Minister Timur Ivanov was sentenced to 13 years in prison and had his property confiscated. Deputy Chief of the General Staff Vadim Shamarin was sentenced to 7 years in a penal colony and stripped of his military rank. According to Carnegie Center estimates, over 30 Defense Ministry officials have been arrested, including three deputy ministers.

To date, independent media have tallied at least a hundred arrests of high-ranking officials and countless detentions of lower-level ones. Virtually every day brings the detention of some official — a vice-governor, a local security officer, or a mayor — and the list of arrests stretches on for dozens of pages. Experts note that this campaign is being conducted with little fanfare, despite its colossal scale. “For an autocracy to survive, it needs to instill fear, but not spin up the machinery of Great Terror,” says prominent Russian political scientist Yekaterina Shulman. The authorities avoid publicly calling these actions a “purge” and scarcely cover them on television. Yet the risks for officials are enormous. The number of cases is growing rapidly, it’s impossible for them to leave the country safely, and a redistribution of portfolios and positions is underway. Paranoia and fear have swept through Russia’s elite — just as in the Soviet Union of the 1930s.

Oligarchs in the Crosshairs

The security apparatus’s crackdown has targeted not only officials but also big business. On July 6, the day before Starovoit’s suicide, the FSB arrested Konstantin Strukov — a billionaire and former regional deputy — at Chelyabinsk Airport as he was about to depart on a private plane. Investigators found foreign passports in his family’s possession and evidence of money transferred abroad — all of which the authorities have framed as criminal. This is the third arrest of a billionaire this year: earlier, agribusiness magnate Vadim Moshkovich landed behind bars, and tech oligarch Sergei Matsotsky was placed on a wanted list. In parallel with arrests, the Prosecutor General’s Office launched a mass “seizure for future selling” of Strukov’s assets. On July 3, it moved to nationalize five major private companies (including key gold-mining empire, Yuzhuralzoloto) and to partially seize the assets of six more. The total value of the targeted assets is around $2.2 billion. The formal justification is a fight against corruption and “illicitly acquired” property, but in essence the state is simply taking over attractive businesses from their owners.

This purge is gradually reaching the very top of the power hierarchy. On July 18, Moscow’s Basmanny District Court charged IT entrepreneur Sergei Matsotsky — a close associate of Prime Minister Mishustin — in a bribery case, issuing an arrest warrant for him in absentia and placing him on the wanted list. Matsotsky owes much of his career to Mishustin, and Mishustin in turn owes much to Matsotsky. Together they oversaw the highly successful digitization of the Federal Tax Service — one of Putin’s flagship projects — which paved Mishustin’s way to the prime minister’s post. Just a year ago, someone of Matsotsky’s stature — whose former subordinate is now the Minister of Communications — would have been untouchable. But times have changed: the FSB is working its way up the hierarchy of power.

Apart from arrests, there has been a spike in “mysterious” sudden deaths of senior executives at state corporations and among business leaders. In the last three months alone, a series of high-profile deaths has struck Russia — including executives from Transneft and Uralkali (one of the world’s largest potash fertilizer producers). Especially notable was the sudden death of the 56-year-old founder of Samolet, Russia’s largest real-estate developer. Rumor had it that the company was closely connected to the governor of Moscow Region — another figure who until recently would have been considered “untouchable.” Samolet, as the country’s largest developer, made a fortune during the era of ultra-cheap, state-subsidized mortgage programs. The end of those programs — combined with rising interest rates and a collapse in consumer demand (despite nominal revenue growth in 2024) — led to rumors that Samolet was in trouble and might need a state-funded bailout. Amid these troubles, law enforcement took interest in the firm: Russia’s Investigative Committee raided its offices and opened a number of criminal cases — signaling the start of a new wave of “nationalization.”

Since the war began, Putin’s regime has made it clear to the business community that no capital is safe — even wealth built independently of the state can be seized. It is yours only until the state decides to take it away. A telling precedent came in June with the nationalization of the company behind the wildly popular game World of Tanks. Moscow’s Tagansky District Court transferred 100% of the shares of Lesta Games — the Russian studio that develops World of Tanks — to the state, while simultaneously declaring its executives “extremists.” For the first time, a fully private, non-oligarchic asset was seized by force — a direct signal to all entrepreneurs that even businesses built “independently” are not untouchable.

FSB’s Stalinist Revival

Meanwhile, the security apparatus is seeking to reclaim the powers of the KGB. In July, the State Duma (Russia’s parliament) passed a law that effectively revives the late-Soviet KGB’s prison empire. As of January 1, 2026, the FSB will once again have its own pre-trial detention centers — special prisons reserved exclusively for “political” defendants. These special pre-trial detention centers (SIZO) will house those charged with “crimes against the state” — treason, espionage, sabotage, terrorism, “discrediting the army,” extremism, and so on. In other words, anyone deemed “dangerous” to the regime can now be isolated from the outside world under full FSB control. This reform portends extremely harsh conditions of confinement. “We will not learn anything about these people — whether they are being tortured or even fed,” warns expert Anna Karetnikova, explaining that moving SIZOs under FSB control means total isolation and even depriving prisoners of the right to correspondence.

This law rolls back restrictions introduced in the 1990s to satisfy the Council of Europe. Prisons are being transferred from the Justice Ministry back to the FSB — along with the FSB’s right to transport prisoners and use force against them. Now the “Chekists” will be able to officially use special measures against detainees — “in the event of an attempt to escape or resistance.” In effect, the security services are building a “state within a state”: the FSB will have its own network of prisons and transport units, its own rules of confinement, and even its own system of medical care for prisoners — all outside the supervision of the Justice Ministry and the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN). The only thing missing to complete the NKVD tableau are the “troikas” — the extrajudicial three-person commissions Stalin used during the Great Terror to issue rapid convictions.

Human rights advocates point out that returning prisons to the FSB means placing hundreds of detainees in conditions of zero oversight — effectively, a new Gulag. This system has already been test-run at a “filtration” prison in Taganrog, where the FSB holds an unknown number of Ukrainians illegally abducted from occupied territories — entirely outside any legal framework. Sparse media reports and survivor testimonies indicate that torture is routine there and that FSB operatives exercise no self-restraint. Analysts note that tortures are becoming normalized in Russian news — from the near-fatal beatings of detained terrorists who attacked Crocus City Hall, to cases this summer of members of the Azerbaijani diaspora being brought to court bearing signs of torture. The system not only fails to hide these abuses — it flaunts them.

At the same time, the role of FSIN (the regular prison service) is diminishing: in 2025 alone, 19 correctional colonies were closed, the total number of convicts under FSIN jurisdiction fell, while the number of prisoners in SIZO grew. In other words, the penal system is shifting: more people remain perpetually “under investigation” in SIZO — including in the new FSB-run facilities — instead of being convicted and sent into the regular FSIN system.

Criminalizing Dissent

Repressive laws are also targeting ordinary citizens. Since 2022, Russia has enacted dozens of new prohibitions, and this trend only intensified in 2025. The FSB’s rising influence has coincided with an avalanche of new criminal cases for “state treason.” In 2024 there were 145 convictions for treason — a record for the post-Soviet era. In 2025, new “treason” cases are being opened almost daily — at a pace not seen since Stalin’s time. The treason cases themselves are completely classified: state media barely report on them, and the charges and sentences are kept secret. As the outlet Kholod notes, even publicly mentioning that someone was convicted of treason can itself be construed as treason — and bring a fresh charge. Relatives of those convicted are afraid to speak even privately about such cases, for fear of drawing attention themselves. All of this is creating an atmosphere of fear and despair in the country, much like the late 1930s.

The severity is seen not only in the growing number of cases, but also in the punishments: since 2023, anyone convicted of “treason” receives at least 12 years in a high-security penal colony — an unprecedented harshness in recent Russian history. On July 14, 2025, the Second Western Military Court in Moscow sentenced writer Boris Akunin in absentia to 14 years in a strict-regime colony — a high-security prison in Russia’s system. This absurd verdict (Akunin left Russia long ago) is telling: never in recent memory has a writer in Russia received such a harsh punishment solely for words. Officially, he was accused of “justifying terrorism” and violating the “foreign agents” law — but in reality, he was punished for his anti-war stance.

Anyone ever connected with the opposition or who has criticized the regime is coming under attack. After crushing independent lawyers and liquidating NGOs and human rights groups, the authorities moved on to the last bastions of free thought in journalism and culture. Across the country, even regional media outlets and educational spaces that tried to remain neutral are being shut down. This spring and summer saw a wave of raids and arrests that swept up even long-apolitical organizations — from small-town news portals to lecture halls and art spaces that, just a decade ago, hosted public debates.

In August, the purge even reached pro-government Telegram channels. The popular hawkish channel Readovka was abruptly re-registered under a Kremlin-linked manager, and its former owners and editors quit — reportedly under pressure from the Investigative Committee. Around the same time, the offices of another channel, Baza — known for its ties to the security services — were raided. Journalists there were searched, and editor-in-chief Gleb Trifonov was arrested on charges of bribing sources for information. Loyalty is no longer enough; the regime now demands total submission across the media landscape.

Digital Iron Curtain

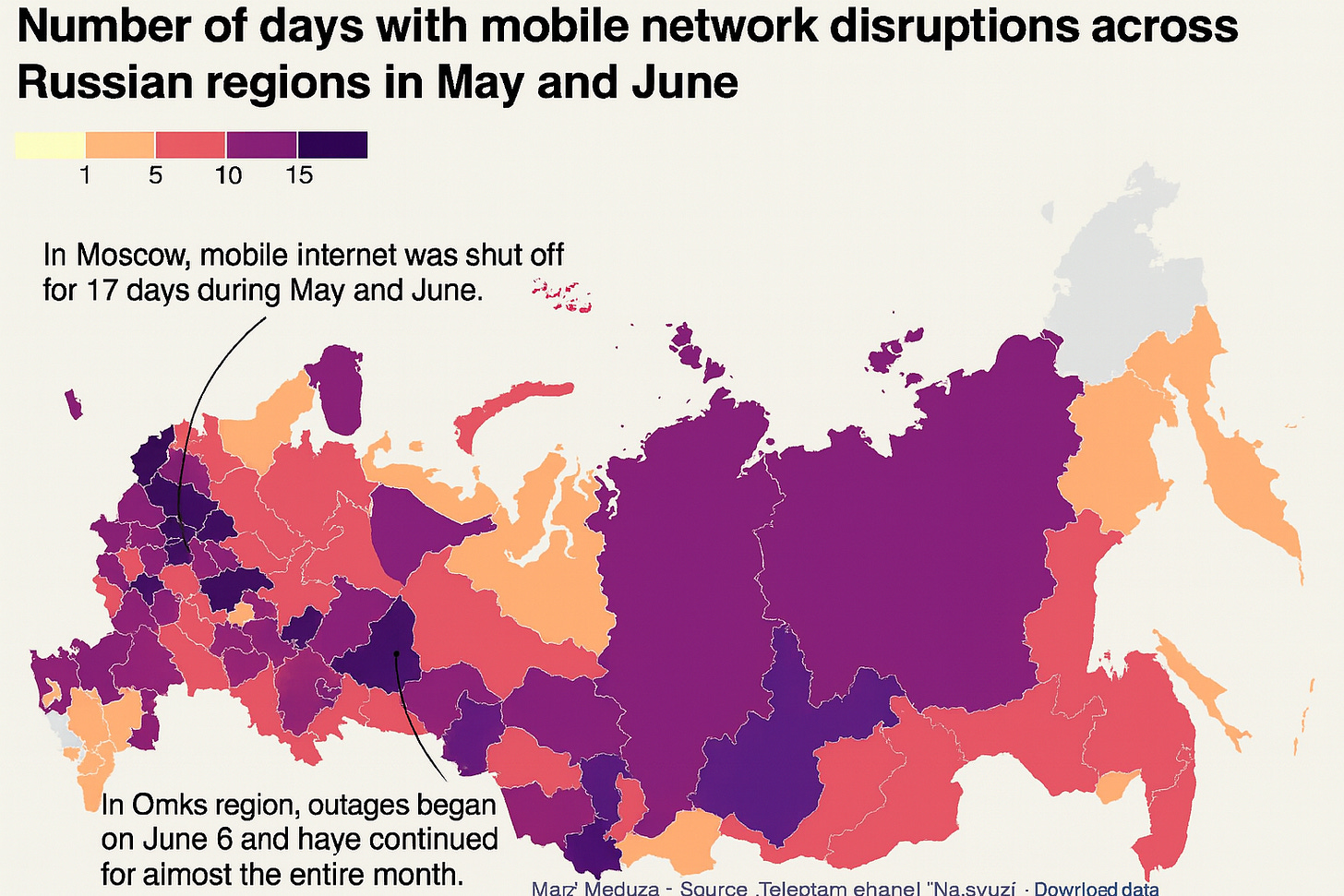

Total control is extending into the digital realm as well. Throughout the summer, regions across Russia experienced periodic mobile internet shutdowns — the independent monitor At Connection recorded over two thousand such incidents. Officially, authorities blamed these outages on “attacks by Ukrainian drones” that could allegedly use cellular networks for guidance. However, the timing of many shutdowns did not correspond to actual air-raid alerts, and their duration (sometimes several days) was clearly excessive for repelling drone raids. Even far-flung regions — from Bashkiria to the Far East, thousands of kilometers from Ukraine — were subjected to shutdowns. In some areas, mobile internet was down for multiple days straight (with record in Omsk region for almost entire month), causing everyday services to collapse: people couldn’t withdraw cash, pay for purchases via apps, or even open parking gates. Shutdowns hit both major cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, and countryside.

Observers have hypothesized that authorities are gradually acclimating citizens to doing without connectivity. This theory gets some backing from a government initiative. Under the pretext of these “anti-drone” measures, the Ministry of Digital Development and telecom operators agreed to create a “whitelist” of internet services that would remain available during a shutdown, while everything else — social networks, independent media, foreign sites — would be cut off by DPI filtering. In August 2025, the government officially acknowledged partially blocking VoIP calls on WhatsApp and Telegram. Roskomnadzor (the state communications regulator) announced it was restricting voice calls in these apps due to “an increase in their use by fraudsters” and the platforms’ “failure to comply with requirements.” Independent experts directly tied this measure to the promotion of a new state-run messenger called “Max.”

This state-sponsored WhatsApp analogue, developed by VK (a state-aligned tech giant), is meant to become the nation’s unified messaging platform. Authorities tout it as “secure,” and it is already becoming mandatory in numerous institutions. Orders are spreading to migrate official chats — as well as school and parent groups — onto Max. In effect, Russia is preparing a closed national messaging ecosystem under full state control.

The regime is also attacking the last tools Russians have to bypass censorship. Since 2022, authorities have systematically blocked major VPN services and protocols. And starting September 1, 2025, a direct ban on advertising VPNs comes into force, with fines up to 500,000 rubles (about $5,000). Tellingly, even VPNs may not save users: officials have learned to block specific encryption protocols. For example, at the end of 2024 Roskomnadzor compelled companies to disable the TLS ECH encryption extension — which Cloudflare’s CDN uses by default — because it allowed users to evade censorship. In February 2025, Cloudflare was forcibly added to the registry of “information dissemination organizers” (ORI), after which its traffic in Russia fell by 30%. Thousands of websites relying on Cloudflare’s network slowed down or became inaccessible to Russian users. Before that, Russian authorities had similarly throttled YouTube — causing view counts to drop and pushing more people back toward state TV.

Since 2019, the Kremlin has been developing “mechanisms for centralized traffic management” — essentially an internet kill switch to disconnect the domestic web from the outside world. A data-localization law is already in force, requiring any website holding Russian users’ data to house servers inside Russia. Meanwhile, all internet exchange points have been consolidated into a few locations under Roskomnadzor’s control. If those are switched off, Russia’s connection to the global internet would be severed. In 2025, authorities conducted drills to completely disconnect Russia’s segment of the internet from the global web — testing the so-called “sovereign Runet.”

In tandem with the VPN ad ban, Russia has for the first time created liability for the very consumption of content. As of September 1, 2025, intentionally searching for “extremist materials” — broadly defined as not only anything on the official extremist list but any content produced by “extremists” — is an administrative offense. Given the usual trajectory, criminalization will likely follow. And just recently, a bill was submitted to the Duma obliging all internet platforms operating in Russia, from 2027 onward, to monitor users and be held responsible for failing to report “offenses” on their platforms. Russia is marching rapidly toward digital isolation on a par with Iran or North Korea.

Closing the Exits

This clampdown on freedoms has also extended to the right to leave the country. Until recently, millions of Russians took for granted certain fruits of globalization: vacationing in Turkey, sending their children to study in Europe, or freely moving their savings abroad. Now those doors are slamming shut. Since the war began, the authorities have swiftly expanded “no-exit” lists. First, they banned travel for all security personnel and civil servants. Then the net widened to include civilian specialists — for example, Central Bank economists, state company executives, and IT staff at sensitive research institutes. In 2024, a secret decree barred key employees of Rosneft, Rostec, Rosatom, and other strategic firms from foreign travel. Earlier, a rule was introduced that anyone with access to mid-level state secrets may travel only to “friendly” countries, and only with written permission from their superiors. By some estimates, these travel restrictions now affect over one million people.

At the same time, barriers have also tightened for men of military age. After the partial mobilization announcement in fall 2022 — which prompted a mass exodus — the government began enforcing new measures on men eligible for call-up. In 2023, a unified electronic registry of conscripts was rolled out. Now, receiving a draft summons automatically blocks one’s foreign travel. This system was piloted in summer 2023 and was operating nationwide by 2024. The validity of a “draft board decision” was extended to a full year. This summer, a bill for “year-round conscription” starting in 2026 was introduced in the Duma — a move that would eliminate the last “windows” when young people might leave between draft cycles. As a result, any draft-aged man can now be stopped at the border — even without an explicit ban — under the pretext of “checking mobilization status.”

Having worked to lock in potential conscripts, the state is already contemplating new steps. Lawmakers are even discussing an “exit tax” — for now, a symbolic fee of 100–300 rubles (just a few dollars) per trip. For the time being, it’s only a token proposal, but the very fact of it shows the regime’s desire to make foreign travel less attractive and more burdensome.

Not only physical movement but cultural exchange has come under attack as well. Since the war began, the last remaining foreign cultural centers have been forcibly closed, and international tours and festivals have been canceled. The notorious “naked party” case led to an example-setting crackdown on the entertainment industry for “immorality,” followed by new campaigns to “protect traditional values.” Russia’s pop music and film industries are being rapidly “patriotized”: the remaining artists must demonstrate loyalty to avoid losing state funding and venues. Films and series featuring actors deemed “unreliable” or labeled “foreign agents” are being banned from distribution and scrubbed from domestic streaming services. And foreign films in theaters may soon be all but gone — the Culture Ministry is discussing quotas to cut the share of foreign releases to a token level. At every turn, the public is being told that a true patriot’s place is at home, and that ties with the West verge on treason.

Militarizing Youth

In parallel, the state is intensifying its ideological indoctrination of young people — effectively militarizing the next generation. Since 2023, universities have introduced new mandatory courses like “Foundations of Russian Statehood,” aimed at instilling a “proper” understanding of Russia’s role in the world. In schools, a Soviet-era practice was revived in late 2022: the post of deputy principal for “educational work” was created, often filled by retired security officers or loyal officials tasked with monitoring ideological purity.

Militarist propaganda is being woven into education. Since September 2022, schools have held weekly “Conversations about Important Things” — patriotic sessions where the state’s position on current events is delivered. Topics range from “the heroism of participants in the Special Military Operation (SVO)” to “traditional spiritual-moral values.” (SVO is the Russian state’s official term for the war.) Starting September 1, 2025, these talks are even being rolled out in kindergartens for children as young as three. The Education Ministry confirmed that in several regions (Moscow, Chukotka, Perm Krai, etc.) pilot sessions will be held in which teachers “in accessible form” will tell children about goodness and friendship — and, of course, about love for the Motherland and respect for Russian history. Education Minister Sergei Kravtsov put it bluntly: “We need to work with children now so that others don’t start working with them later” — a clear signal that the state does not intend to leave even preschoolers outside its ideological reach.

Russian children are quickly being militarized. Schoolchildren are being taught that war is normal: across the country, “SVO heroes” visit schools, “Our Victory” lessons are conducted, and children are urged to join Yunarmiya — a state-sponsored patriotic youth organization with military-style activities and symbols. At some schools’ graduation ceremonies, students even traded the traditional white pinafores for military uniforms. In some kindergartens, journalists discovered that as early as 2024 children were being shown portraits of Putin and taught about the “special military operation.” At universities, students are indoctrinated to be ready to sacrifice themselves for the state, and new military training centers are being established on campuses. In short, the authorities are preparing the young for a protracted confrontation with the outside world. The generation of the 2020s is being raised under a militaristic, isolationist ethos reminiscent of the late USSR.

Alternative views are harshly punished — several high-profile cases have shown the system’s rigidity. Schoolchildren and students who posted anti-war comments or spoke out against the bloodshed in Ukraine have been expelled and put on watch lists, and their parents prosecuted for “improper upbringing,” sometimes even sent to prison.

Putin’s Permanent War

Adding up all these trends leads to one conclusion: under Vladimir Putin, Russia is irreversibly transforming from a mere authoritarian regime into a new kind of digital totalitarian state — and even an end to the war in Ukraine will not return it to its previous form. Many in the West hope that after peace, Russia will “return to normal” — rolling back repression and reconciling with Europe. But that is pure illusion.

This internal transformation has already gone too far to undo. The old social contract has completely collapsed. Previously, everything was permitted except what was prohibited. Now, increasingly, everything is prohibited except what is permitted. Money and privileges are flowing to the security apparatus, while business owners and regional elites live under the constant threat of criminal cases. The digital sphere is now thoroughly surveilled and filtered by the secret services — Pyongyang-style. Society is being militarized; children are explicitly being prepared to become soldiers who “must die for the Motherland.”

The very notion of normal life has changed: familiar urban pursuits — theater, lectures, a free internet, vacations in Europe — have become things of the past. Now, only what the authorities approve is allowed. The new whitelists of applications are a literal illustration of this principle. The laws adopted in 2025 — aimed at 2026–27, from FSB prisons to Runet isolation and other new restrictions — are built for the long term. It’s clear that this course of purges and self-isolation is strategic, not a momentary reaction to military challenges.

The hard truth is that Putin has come to love war — peace no longer interests him. In his view, war has become “the optimal solution,” rallying society around him and allowing him to crush the opposition. At home, he has managed to tighten every screw and finally erase the so-called opposition. The elites are toeing the line, and “USSR 2.0” is being built at full speed. We already see a nearly complete “sovereign internet” in the North Korean mold, and a “revived KGB” — the FSB with its own prisons, investigators, and doctors. We also see a large-scale redistribution of property in favor of those close to the regime. Armed with such tools, a time of peace becomes a frightening prospect for the regime. Without an external enemy, how would they keep the people obedient? If the wartime footing were relaxed, what would occupy the bloated security apparatus? The Kremlin has evidently decided not to find out. Even if the fighting in Ukraine stopped tomorrow, there would be no “thaw.”

On the contrary, the logic of self-preservation dictates intensifying repression to prevent any “fermentation” during a transition. Putin has essentially set an irreversible machine of self-isolation and repression into motion. He is hurtling Russia full-speed backward into the worst practices of its Soviet past — and he will not allow anyone to suddenly reverse course. Any attempts to “return Russia to the family of civilized nations” will shatter against a simple reality: today’s Russian authorities see their only salvation in perpetual confrontation and mobilization. Peace no longer interests Putin — he has traded it for eternal war at home.

The West will have to deal with Russia as a totalitarian, revanchist state for years or even decades to come. Any hopes of “taming” or “persuading” Moscow are doomed to fail. It is no longer the country it was before 2020. And the sooner world leaders accept the irreversibility of these changes, the more sober and effective their policies toward this new, harsh Russia will be.